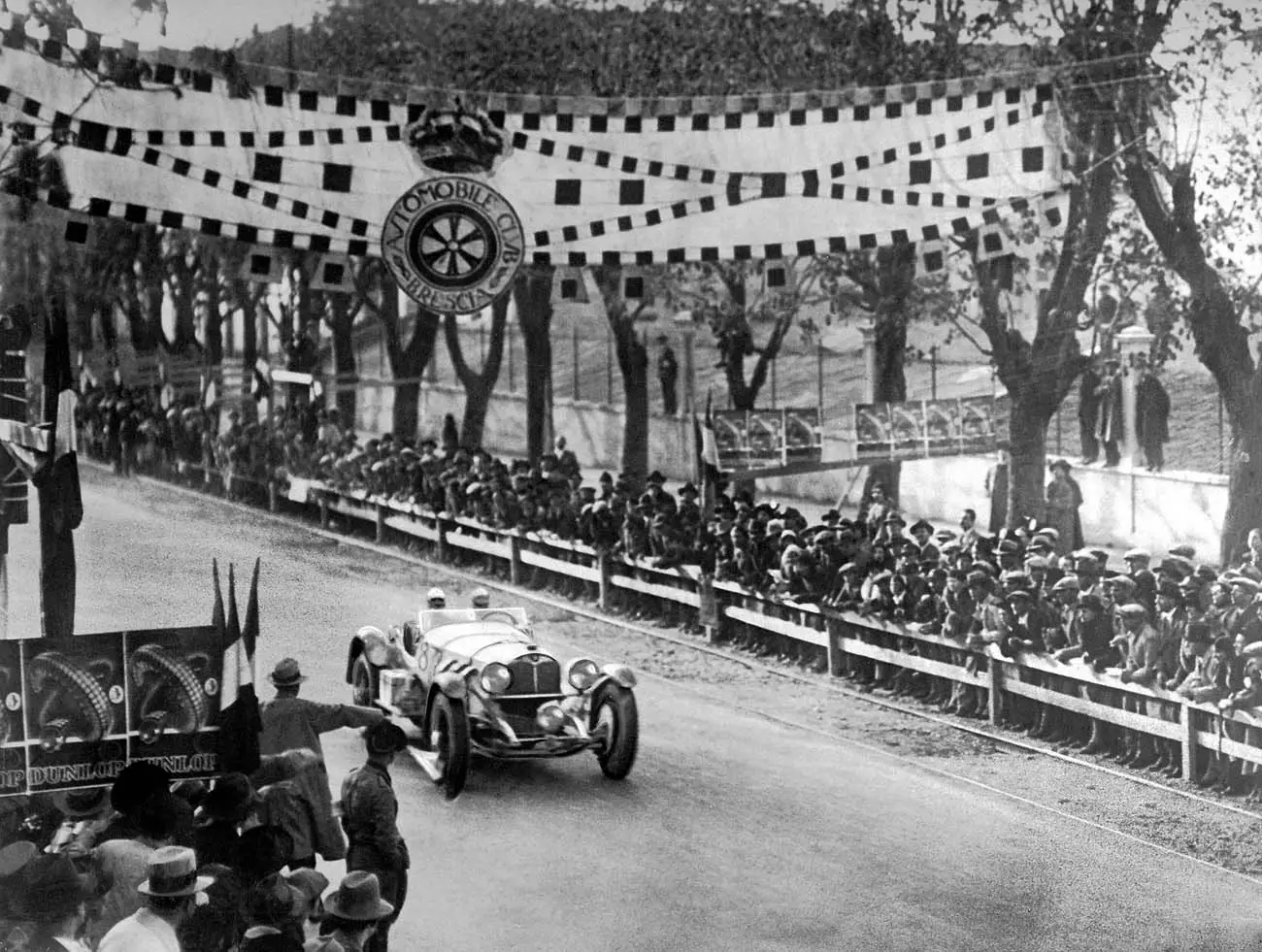

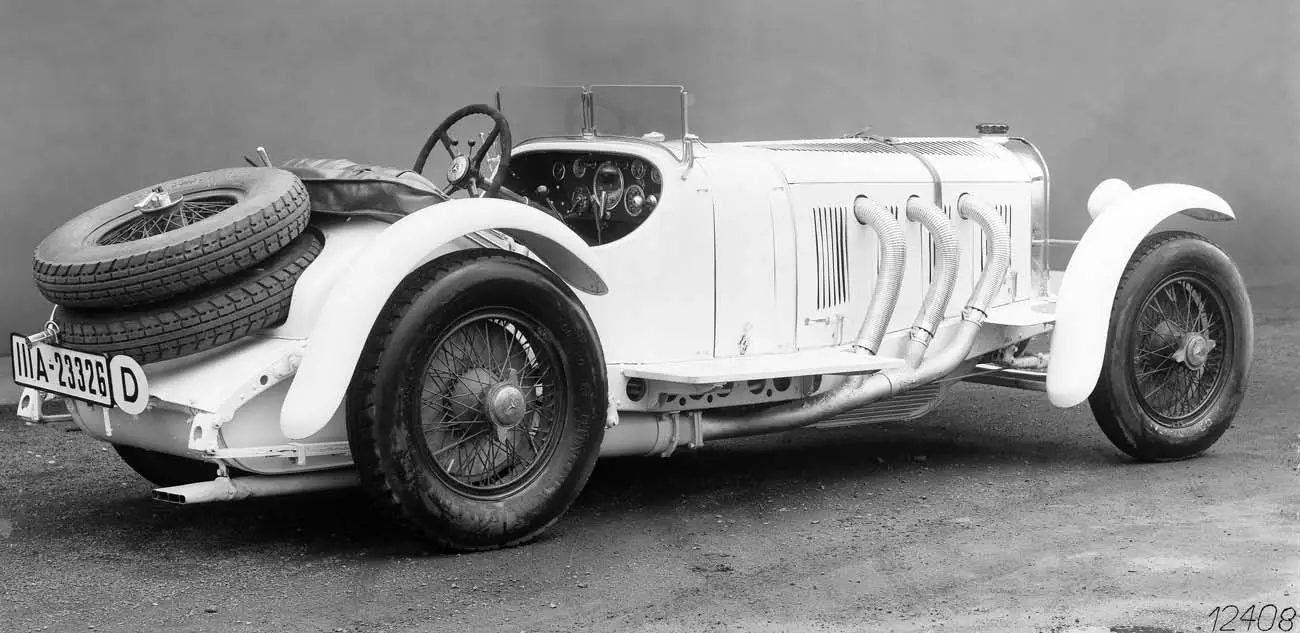

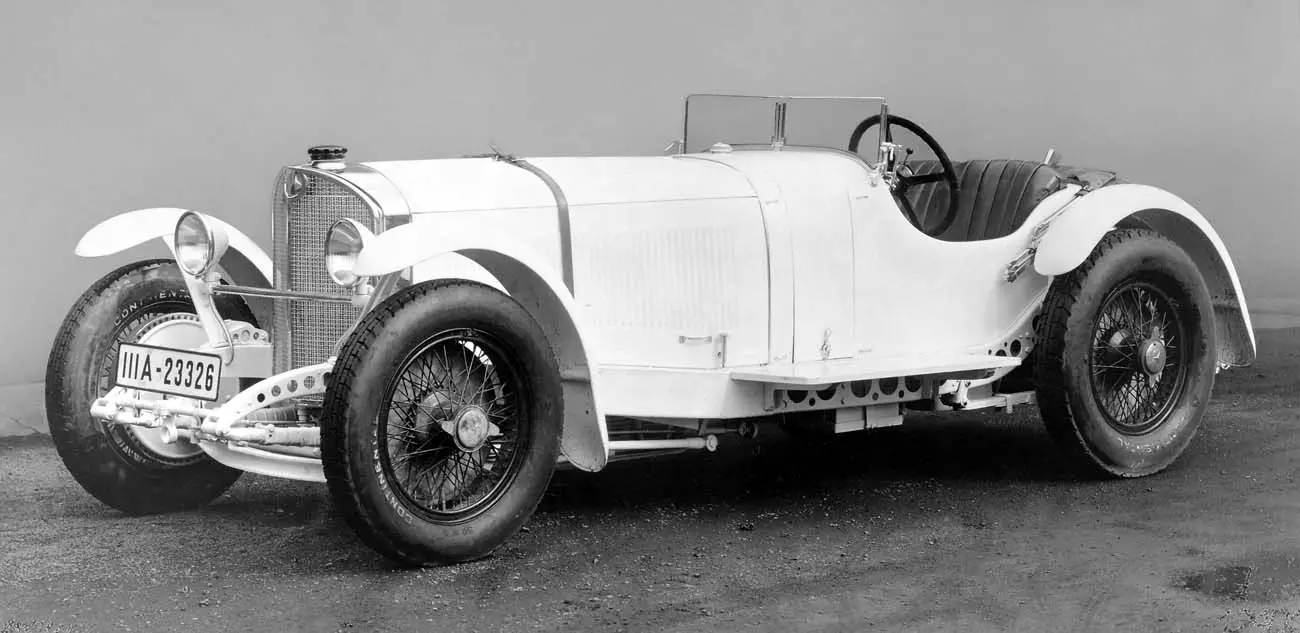

90 years ago, Mercedes-Benz won the 1931 Mille Miglia with Rudolf Caracciola in the SSKL. Two major milestones were achieved in this year, the first non-Italian to win and the 100 km/h average speed was broken.

The victory was something of a surprise. The SSKL was a large and heavy car, despite many weight saving measures, but still beat everything else. Even with Rudolf Caracciola at the wheel the team were not the favourites to win the event. The Italian competition was strong in the fifth running of the Mille Miglia on the 12 and 13 April 1931.

Against all expectations the Stuttgart entry finished the 1,635 kilometre route from Brescia to Rome and back faster than all the others. So fast they beat the 100 km/h average speed at 101.6 km/h. the conditions on the event were tough and the roads were largely unmade tracks, making this a sensation. The total time was 16 hours, 10 minutes and 10 seconds.

The original Mille Miglia was held from 1927 and ran until 1957. Since 1977 it’s been a regularity drive for historic vehicles. Still a tough event, but not the outright race it used to be.

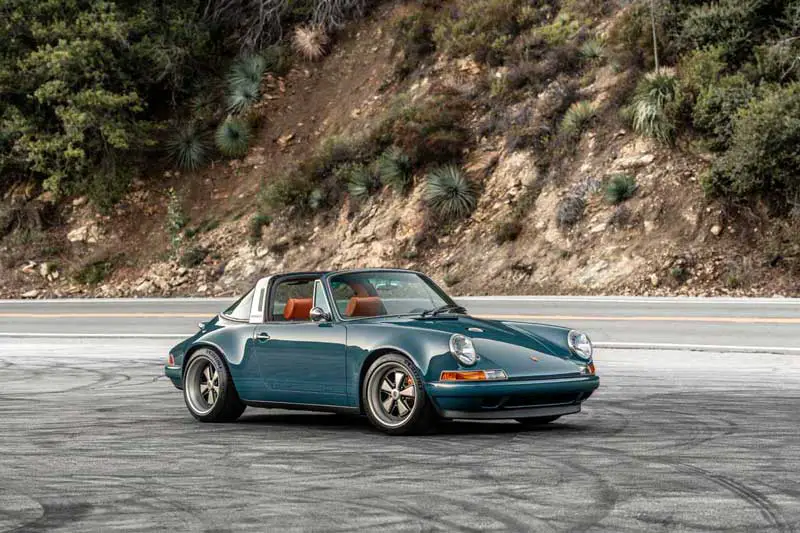

It is one of the world’s most popular events from classic cars. This year the event has been re-scheduled and will run from the 16 to 19 June 2021.

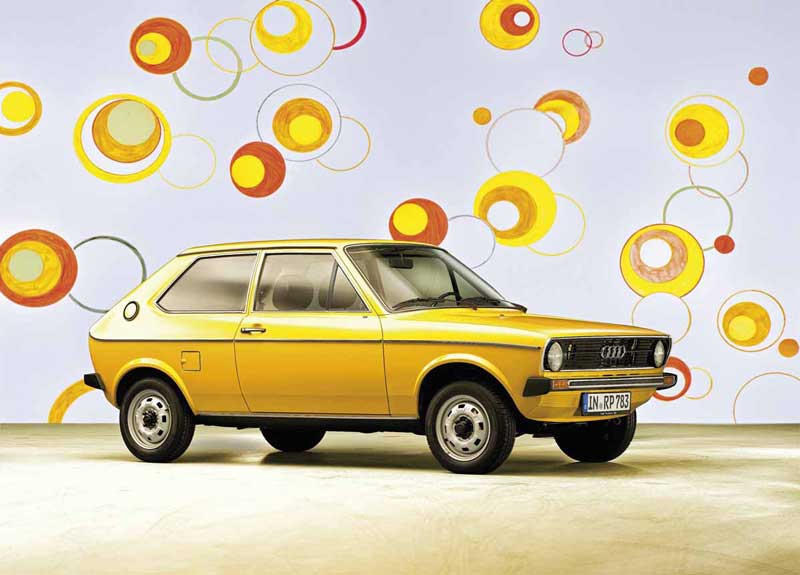

1931 was very different financially. The collapse of the New York Stock Exchange in October 1929 had consequences that were felt world over. In Germany it affected vehicle production which dropped from 39,869 vehicles in 1929 to 88,435 vehicles the following year and then to 64,377 units in 1931. The turnover also fell by about half to RM 68.8 million.

The board of management at Daimler-Benz AG stopped development of the new racing car in 1930 and dismissed driver Caracciola. Even though they won the European hill-climb championship that year. But race director Alfred Neubauer reached an agreement with him that provided for reduced factory support and the provision of an SSKL. In return this meant that Caracciola would work exclusively for Daimler-Benz in races and sporting events during the 1931 sporting year. The 1931 racing programme was more modest than planned but led to eleven victories from eleven starts. The team also defended their title of European hill-climb champion.